Eating at Syracuse University Costs an Arm, a Leg, and a Car

Hunting and Gathering in My $80,000 per year Private University’s Food Desert

by Zoe Hansen

Dec. 2024

Schine Student Center at Syracuse University, photo by Zoe Hansen

As soon as you step on campus at Syracuse University every detail around you exudes wealth. Not only are the sidewalks made of brick, but multiple colors of brick laid out in a pattern you know cost extra, and when you look where the sidewalk meets the street, you can see the curbs are actually cut from huge pieces of marble. Students pass by wearing designer bags and platform Uggs on their way to get a $12 salad at the Schine student center or a $7 coffee on Marshall Street.

If you can afford it, I’m sure you could eat pretty well living off the trendy restaurants on and around Syracuse’s campus, but the problem is that these restaurants are also the only sources of real food reasonably walkable from campus.

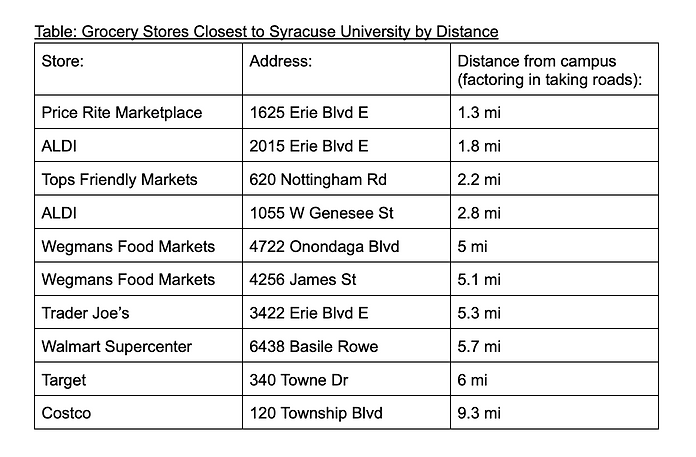

Located in an urban area with a reported 29.6% poverty rate, no grocery stores within a mile of any student housing, and limited public transportation, this $80,000 per year Private University is in a food desert.

For an urban area to be considered a food desert only 33% of the population or 500 residents of the area must live a mile or further from the nearest grocery store.

Syracuse University has over 10,000 students living in this situation.

Students without cars have had to become inventive with how they get their groceries, using a variety of food delivery services, rideshare services, buses, and help from friends.

If an SU student doesn’t have a car, I can guarantee they have a personalized strategy they use to get their groceries, that aligns with their budget, physical ability level, and the time they have available.

Over the nearly six years he's been navigating this food desert, Syracuse graduate student Kai Bason has developed a system to get groceries and get back home in under an hour using Uber.

“Growing up and being in grocery stores with my mom, she would always tell me the longer you are in a store, the more likely you are to spend money and buy more things. So I just trained myself to be quick there,” he said.

Armed with his shopping list and reusable bags, Bason makes trips to Trader Joe’s every two to three weeks.

Each trip he buys enough groceries to fill the three eight-gallon reusable bags he brings, and he often needs an additional paper bag to carry it all.

On his last trip he spent $279.68 on groceries, including seven pounds of ground beef, two gallons of chocolate milk, and five dozen eggs, plus $27 on the uber there and $26 on the uber home.

Bason said he tries to go earlier in the day for more affordable uber fares and a less crowded store, but it all depends on his academic schedule as a grad student and TA.

The uber between campus and Trader Joe’s takes about 10 minutes, and Kai Bason tries to spend no more than 20 minutes in the store.

“Sometimes I get in there and I’m like ‘I’m ‘bout to speed run this,’ like I literally set a timer sometimes,” he said.

The few times he has been able to bring his car to campus, Bason said it made getting groceries much easier, and allowed him to visit multiple stores when grocery shopping.

Last spring when Rohit Jakkula began his graduate degree in mechanical engineering and computer science at SU, he would walk 1.3 miles along the highway to buy groceries at Price Rite.

Bundled up in a puffer jacket and snow boots, this walk took him about thirty minutes each way.

“More than the physical effort it's just the time that it takes,” he told me.

He said the walk was especially hard in the winter and on the way home from the store carrying bags of groceries. Laughing, he admits to having fallen before on this walk.

“Sometimes you encounter ice…you’ve got to be careful,” Jakkula said.

Jakkula has been able to get a car since last semester and he said it has allowed him to shop at the further away stores like Aldi and Costco and to make more frequent trips.

This also eliminated the hour of walking it used to take him to get groceries.

Rohit Jakkula’s story is not uncommon, but most SU students aren’t making that walk along the highway and rely on what they can get from convenience stores around campus and grocery delivery services like instacart and doordash.

Instacart marks the price of grocery items up an average of 15%, and that’s before delivery and service fees, but without the time or ability to reach grocery stores on their own, many SU students use this service to get groceries, making large orders of weeks worth of meals to shoulder the additional costs more easily.

As a humanities student, calculating the most cost-effective method of having my groceries delivered has not been a fun math adventure, but I’ve found that ordering from ALDI through Doordash is a good way to go.

The math that throws me for a loop here is that Instacart has a can of black beans from ALDI priced at $0.95 and doordash has them at $0.99, but when you fill your cart with enough beans to check out, Instacart will charge you $10.99 to bring you your beans and Doordash will charge $6.16.

However, not only does Instacart charge more for delivery, but the prices for groceries aren't always cheaper. I stick with doordash for their lower delivery fees, faster delivery times, and to avoid potential male Instacart shopper experiences.

Another walkability issue for SU students is that the only pharmacy within a mile of campus is the university’s tiny one. The two windows for picking up prescriptions double as the only cash registers in the store, so the line gets long and moves slowly. I have been late to class many times because I was standing in that line to get my meds. The next closest pharmacy is Kinney Drugs, which is 1.7 miles from campus.

The inaccessibility of essentials like groceries and medication without a car puts students who can't afford grocery delivery or ride shares to the store in a tough position where they are reliant on others to access these essential items.

The friend with the car takes on the burden of chauffeuring their friends around the city, and the friends without the car are put in the position of either feeling like a burden by asking for rides or going without.

It's such a tough situation because the car owners on campus really don't owe their car-less peers anything, but they're put in this position where they determine whether the people close to them go hungry or unmedicated. That's a lot of weight and responsibility to carry, plus it costs them time that they may not have in their schedules.

Syracuse University’s Student Association offers free shuttle buses from the College Place bus stop every Sunday, but you have to do it on their schedule, which is not fast – the first shuttle back to campus doesn’t leave until an hour after bringing students to the store.

From College Place, students living off campus must either walk home with a week’s worth of groceries or wait for a bus that can bring them a little closer. Also, Sundays are when the bus schedule is least consistent, so even the wait can become time consuming.

“I mean, I think people forget that time itself can be a barrier,” April Lopez told me.

She is the Assistant Dean of Students, Basic Needs Case Manager, Homeless Liaison at SUNY Oswego, where she oversees the campus food pantry, and works with students experiencing food and housing insecurity. April Lopez is also a graduate of SU’s Food Studies Master’s program.

As a grad student at SU, Lopez did her research on food insecurity among college students, surveying 445 students from Gonzaga, where she did her undergrad, and traveling west to interview eight in person.

Her findings? College students who struggle the most with food insecurity are the ones working multiple jobs.

“You would think, oh, you're working, you make an income, you would be able to afford food but in reality the students struggling the most are the ones who are working the most because they're trying to make ends meet,” Lopez said.

Even if their tuition is taken care of, it is common for college students to step into financial independence when they enter college, working jobs on and around campus to afford living expenses like rent and groceries.

Part of April Lopez’s job is to help SUNY Oswego students apply for SNAP. She said most of the students she meets with about applying are working two to three jobs.

Many college students believe they aren't eligible for SNAP since their parents still claim them as dependants on their taxes, however students from out of state are considered dependants of their university while on campus

It is also common for college students to think they aren’t SNAP-eligible because they are on meal plans or are claimed as dependents on their parents’ taxes or not working enough hours, but the program’s nuances make eligibility easy to be wrong about. Students from out of state are considered dependents of the institution they attend, regardless of their dependence on parents, and students on meal plans covering less than 50% of their meals are not considered residents of the institution, putting them in the same position.

As for employment, students working 20 hours or more each week and students eligible for work study who work any number of weekly hours are eligible.

Learning this made me realize that a lot of my friends could be eligible for SNAP, but if they don’t have cars to reach Syracuse’s SNAP-eligible grocers, does it make a difference?

Basically, if you're on SNAP you’d better also have a car because the stores that accept EBT payment and have real groceries are not accessible without one. Delivery services like Instacart, and Doordash, also accept EBT, but their markups and service fees make these services an unreasonable option for someone already struggling to afford food. Also, since EBT cannot be used to purchase any hot foods, all the restaurants on and around campus are not an option for students depending on SNAP to eat.

There are two places on campus where you can allegedly sometimes buy vegetables, but they will be deformed and you may get locked in a basement.

South Campus Express is the SU-owned convenience store in Goldstein student center where you can find severely overpriced laundry detergent, frozen meals and sometimes score the rare fresh vegetable.

Located in the underground tunnel connecting two freshman dorms and a dining hall, Food Works is the University’s other convenience store, and your only hope of buying a vegetable on main campus. To reach it you must first climb Mount Olympus. No, I’m not kidding – this place is on top of a huge hill by that name, and you will be winded from the climb.

To access the underground tunnel, you either need to live in the dorms or run through the door after a resident scans their ID to open it.

Prasanna Dixit is in his first semester of grad school at the iSchool, and an employee of Food Works, and Graham dining hall. He told me it is usually pretty empty during his shifts, but the evenings are the busiest. He said Celsius energy drinks are easily the item he sells most, followed by frozen burritos.

There weren't any fresh vegetables when I stopped by, but when I used to live on the Mount, I remember the case that is now filled with Celsius used to be where the store kept their misshapen avocados. Dixit said they still sell fresh vegetables, but there were none in sight and no empty spaces or cases to indicate the store was equipped to carry them regularly.

On my way out I discovered that not only does a resident of the attached dorms need to scan their ID to get in, it takes an ID to get back out again too. So I stood there in the tunnel between the locked doors to the dorms and the locked door to the dining hall and waited to be released by an unsuspecting freshman.

I'd hoped Food Works would be a successful stop on my mission to find walkable veggies, but they just seem to have the same things as the convenience store by my house, but further away, and apparently I'm not allowed to leave.

A quick call to SU food services also confirmed that there is actually nowhere on campus that accepts EBT payment, making these convenience stores inaccessible to students who depend on SNAP to feed themselves.

The convenience store closest to my house is called Mr. Orange Market, and owned by Omar Hager.

After moving to Syracuse from Yemen, Omar Hager worked at a gas station for three years before he opened Mr. Orange Market on Lancaster Ave. That was almost six years ago now.

Aware of the sticky nutritional situation of SU students, Hager has made an effort to accommodate the needs of his customers by providing as many essentials as he can to them.

“The students, they have no cars, so we bring all the things here to be easy for them,” he said.

Hager said about 70% of his customers are students, and the vast majority of them come in during the week for the grocery items like milk, eggs, and snacks that he keeps in stock. He has to restock grocery items twice a week to keep up with the demand of the students relying on him for their groceries.

When students leave for the summer the drop in customers is so significant that products of which he would usually order 5000, he only needs to order 1500.

“This area depends about the students, without the students it drops too much,” Hager said, shaking his head.

He told me if a customer comes in asking for a product he doesn’t carry he will order it for them and have it by the next week. I know this is true because he’s done it for me. Last year when Hager told me he’d have the pink rolling papers I’d asked about the next time I came in, I assumed he just meant I should come try again another time, but it turns out that was a promise. The next time I came in Omar Hager greeted me, smiling and waving the little pink package over the plexiglass divider on his counter.

“No, I’m telling you everything they ask, we bring,” Hager said firmly when I had finished rattling off a list of items I wasn’t sure he carried.

As of now, he only has the licenses to sell tobacco, beer, pantry items, and refrigerated items like milk, eggs and cheese – no fresh food or produce.

However, he is waiting to hear back about the license he applied for that would allow him to sell the hot food items, such as burgers and shawarma, that he would like to be able to provide to his customers.

Omar Hager really enjoys being a part of the community and building relationships with his customers. He has even stayed friends with students after they graduated and left Syracuse.

“When you come here, you see people laughing and smiling, joking. This is what you need,” Hager said.

An hour of driving or a day of walking away at Cornell University, students found themselves in a similar situation to those at SU, with their only walkable grocery store being exorbitantly expensive, but unlike at SU, they took action.

In 2017 a student-run store called Anabel’s Grocery opened on campus, strategically placed to be convenient for students to access, and stocked with locally produced foods available at discounted rates, it has made accessing proper nutrition much more accessible and affordable to Cornell students. Anabel’s also accepts EBT!

After efforts to get support from their administration proved fruitless, Cornell students were able to secure funding to open the store from the Center for Transformative Action, a nonprofit incubator located on their campus.

The Center for Transformative Action (CTA) is an independent 501(c)3 affiliated with Cornell University which receives 25% of its funding from the Cornell Vice president’s Office and the other 75% from fundraising and donations.

Anabel’s is just one of the 35 nonprofits under the CTA, which takes care of their taxes and legal paperwork.

The store is organized by professor Anke Wessel, the CTA’s executive director since 1988, and the instructor of the entrepreneurship class whose students work on committees to run the store and learn about local agriculture and food systems.

Trisha Bhujle and Ella Wilkinson took the class last year, serving on the Purchasing and Collaboration & Education committees, this year they are coordinators of the Purchasing committee.

Anabel’s keeps its products affordable by running a deficit, supported by a subsidy fund to make up the difference. The vendors still get paid their full rate, the subsidy fund is there to pay the difference between what the store spends on products and what its customers pay.

Major drawing points to Anabel’s include the fresh sourdough loaves that they sell for $3, even though they cost $7 at the local bakery where they’re made, their bulk buying options, and the meal kits they sell for two to three dollars.

Trisha Bhujle and Ella Wilkinson said they plan to step down from their positions at Anabel’s next semester to focus on writing a guide to help students at other colleges create an Anabel’s of their own.

In addition to Omar Hager’s future in hot food, this guide might be just what Syracuse University needs to make progress towards better access to food for its students.